Wednesday, September 30, 2009

"You are going to find that studying Ray becomes a discovery of yourself to yourself, yet also a revelation of yourself to others"

from an email by William S. Wilson

Ray's anagram, so like a code, would isolate him unless he explained or was questioned. To explain THE BAD ARA [a collage by Ray] reaches THEDA BARA and moving images, the visual illusions of films. The name THEDA BARA was advertized as ARAB DEATH in the image-making of Hollywood, as though the name hid a secret. The fact is that the family name "Baranger" was shortened to "Bara." Then, in a familiar but arbitrary operation not implied by any system of language, "Bara" was reversed to "Arab," suggesting that a name could participate in a secret code which excluded people not in on the secret. Changes of name reach visual art with the names Larry Rivers, Mark Rothko, Phillip Guston, Lee Krasner and Andy Warhol -- changes for which no one had any rules to follow. Ray frequently renamed people, bringing them into his field of cross-references as though there are no rules for names. Acting without rules, or against the rules, can seem childish, but a purpose can be an experience, not of childhood, but of childish time.

The name "Eve" is a palindrome, while "Eva" reverses to "Ave," so that the second "Eve," Mary, can be hailed with a palindrome: "AVE EVA." Not everything in language happens for a reason, but almost everything can be made to serve a purpose. Thus accidents of language can be understood as being purposeful, because they seem providential after a purpose has been devised for them. That a person turns up named Letterman or even Mailman combines that person with Ray's on-going themes and images. A man who asked me why Ray had mailed items to him, when he scarcely was acquainted with him, turned out to be named Harvey, as with the rabbit; and another similar man is named Joiner. Once on the Bowery Ray approached the table which had the guest-list for a party upstairs in a loft. When asked his name, he responded, "Mailer, Norman Mailer," and was admitted to the party. Ray subjected words to his purposes by following his rule that a shorter word found in a longer word was part of the meaningful use of the longer word. He found "pond" in "correspond": "The frog jumps into the correspondence" (90 03 22). Thus he found the word "toes" in mottoes, grottoes, and especially potatoes. He could also add "toes" to a word or a name, as he might press two words together, as with "Toby" and "toes, and then rhyme "Tobytoes" with "potatoes." The rhyme makes "Tobytoes" seem to be less of an accident because it is purposeful.

BMCM+AC's Proposed Ray Johnson Show

The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson

In 1948, after three years of study at Black Mountain College (BMC) under Josef Albers and Robert Motherwell, Ray Johnson made the move to New York, following in the footsteps of a long list of BMC avant-garde artists who left behind the blue mountains of Western North Carolina for the urban canyons of Manhattan. For the next decade, Johnson experimented with art—presiding over downtown Manhattan’s “art zoo,” as one critic jokingly put it—addressing the margin through an individual sense of the contemporary highly politicized art scene.

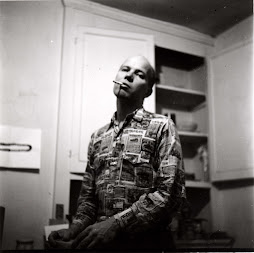

In both settings, first the tight cabal of Black Mountain College, then the downtown art scene in Manhattan, the Pan-like Johnson needed to react to and create out of the people and events swirling around him. “Walking down the street with Ray Johnson,” says artist Billy Name, “all of a sudden you see the world as this wonderful, delightful, joyful, playful place and it doesn't stop…you became part of this joyful world that he lived.” Word soon got out about this playful, sly collagist and postal-art maker, founder and hub of the now famous New York Correspondance School.

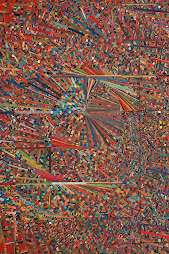

An autodidact student of Buddhism and a self-described disciple of John Cage’s cultivation of chance occurrence, Johnson began as a painter but soon turned to cutting works into slices and uniting them with other elements. Johnson’s recycled collages combined canvas strips with text and images from popular culture—James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley—in a manner that anticipated the 60s Andy Warhol. In her text, Ray Johnson: Correspondences, Donna de Salvo compares Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines to Johnson’s early collages, noting, “If Rauschenberg introduced life into art, Johnson introduced art into life.” After Marcel Duchamp, Ray Johnson was one of the first artists “to utilize instructions for active participation in the artwork into the artwork itself.” His interest “in codes, poetics, and semiotic systems looked back to Duchamp while anticipating the contemporary practice of appropriation.”

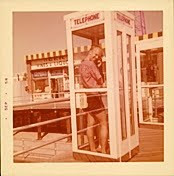

Over the next decade, Johnson made a series of anti-rectangle collages. It wasn’t long before Johnson was mailing out collage fragments “for others to use or send on,” letting go authorship (at least in part) and allowing the work to be formed by increasingly random collaborations. No coincidence, then, that Johnson made this creative leap during his transition from Black Mountain to New York City while hanging out with his BMC buddies. Though a vital and experimental community, Black Mountain College was a bit of a mirage, isolated in many ways. For such an event-based artist, the late night dances were great but couldn’t beat the Ur-city’s cornucopia of experience that provided Johnson with such abundance. In both instances, he was surrounded by artist friends and mentors, immersed in their scenes. “With Manhattan as his field,” William S. Wilson writes, “Ray was disciplining himself to find uses for almost any accidental event.”

With all the myth and lore surrounding Ray Johnson and his theatrical suicide, it may seem to a young artist today that Johnson popped, fully formed, out of the head of modern art. But of course, as with all great artists, the young Johnson has his training ground. With our proposed show, “From BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson (1948-1958),” we will trace a circle around a decade of Johnson’s early art, spotlighting his explosion from talented painter and master collagist status to, by the 60s, Grand Dean of Dada & Postal Art. Indeed, Johnson’s time at Black Mountain College can be viewed in retrospect as a platform from which he dove into the vibrant world of New York City and its art world.

BMC-era piece

from an essay by Arthur Secunda

Ray Johnson was a friend of mine when we were about 14 years old at Cass Tech High School in Detroit. We were wild about art of all kinds and both went to Saturday art classes at the Detroit Art Institute where we had a wonderful young teacher from Wayne State, who taught us everything from quick sketching to casting our own sculpture with molds. I also took classes at Wayne in addition to our difficult art studies at Cass. Ray took classes somewhere else too, but I don’t recall where, though he refers to them in some of the letters he wrote in 1943 after I moved to New York.

We had many mutual friends, among them Harry Katchadoorian stands out, a gifted young man who was freer than we were in art, but I lost touch with Harry. Various other friends from school are referred to often in Ray’s letters to me, and I frequently wonder whatever became of them as I reread the letters and the warm affection we held for each other, not to mention the teachers, Ms. Green in particular. She taught art at Cass for generations, a taskmistress who we loved, feared, and respected.

Ms. Green used to give us assignments to draw from life. Among these, I recall her asking each one of us to draw and paint whatever was across the street from where we lived. A terrific bit of homework for a 13 and 14 year old. Another was a 2 week project in charcoal study: she would line us up in the long shiny Cass hallways with metal lockers on each side, and have us render in detail every odd reflection and glistening piece of tile and shiny linoleum as realistically as we could. It was frustrating learning to “see” this way, but great discipline.

Ray often made a big deal about the girls, all girls. I probably did as well. We were really naïve, but then so were the girls but maybe not as much as we. Ray loved to satirize the outlandishness of such glamorous female stars of the day as Carmen Miranda, Lana Turner and Gypsy Rose Lee, among others. We joked, drew and painted the marvelous colors we thought Hollywood reflected. Handsome men like Gary Cooper were also included in our carnival of cartoons of the day.

I recall Ray as always smiling shyly, with a terrific pun or visual thought. However, as serious about being an artist as one can imagine. This personality quality affected my own budding esthetic attitude and others who were attracted to Ray as well.

World War II was in full blaze and though we were aware of the fighting, none of this seemed to seep into our developing art, except for a cartoon or satirical drawing now and then of good guys versus bad guys. My brother Ken, enlisted in the army, and my mom and I moved to New York City in early 1943. (My dad died when I was 5 years old)

At first, we lived on West 82 Street on Broadway, and later moved to 140 West 71 Street between Broadway and Columbus Avenue in a one-bedroom apartment. I think Ray wrote me when we were still on 82 Street but I haven’t found those letters yet. I do remember the mailman delivering mail to our door at apartment 3B, with a broad grin and some friendly comments when Ray’s letters started appearing every day, sometimes twice in one day. He liked to bring the letters to our door rather than leave them downstairs to be crushed in the mailbox. I believe he sensed these messages were more than mere communications.

Of course, I wrote Ray very often too, and when I skipped a day, he would complain. He also gave me “lessons” by mail, urging me to be more serious in my art to him and stop cartooning, or to take more time with certain techniques. All his letters and cards were joyous and upbeat. His poetry was infectiously absurd and dada. Long before he went to Blackmountain College or studied with Albers, he showed the sort of natural ease and self-acceptance of being talented and exceptional.

Cuttings from Catalogue Essay (An Introduction)

Maybe because I am a writer and a collagist myself, there appears no other way to do approach Ray’s work but to track his creative process as he moves from place to place. Ray’s friends, it seems to me, accepted Ray for what he was not what he could or should be. They lived his limitations as he lived with theirs. (Secunda told me that he ever shy Ray looked you not in the face but “in the mail.”)

Bill on Ray, in his article: “Ray’s collages conceal any depths in order to reveal his satisfactions with surfaces. Surfaces suffice, in his experiences and in his art, both of which are finite, but unbounded.”

+copy.jpg)