The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson

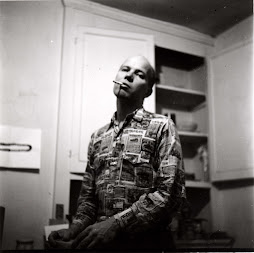

In 1948, after three years of study at Black Mountain College (BMC) under Josef Albers and Robert Motherwell, Ray Johnson made the move to New York, following in the footsteps of a long list of BMC avant-garde artists who left behind the blue mountains of Western North Carolina for the urban canyons of Manhattan. For the next decade, Johnson experimented with art—presiding over downtown Manhattan’s “art zoo,” as one critic jokingly put it—addressing the margin through an individual sense of the contemporary highly politicized art scene.

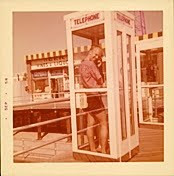

In both settings, first the tight cabal of Black Mountain College, then the downtown art scene in Manhattan, the Pan-like Johnson needed to react to and create out of the people and events swirling around him. “Walking down the street with Ray Johnson,” says artist Billy Name, “all of a sudden you see the world as this wonderful, delightful, joyful, playful place and it doesn't stop…you became part of this joyful world that he lived.” Word soon got out about this playful, sly collagist and postal-art maker, founder and hub of the now famous New York Correspondance School.

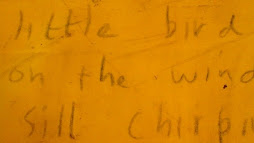

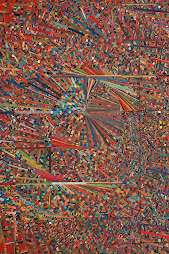

An autodidact student of Buddhism and a self-described disciple of John Cage’s cultivation of chance occurrence, Johnson began as a painter but soon turned to cutting works into slices and uniting them with other elements. Johnson’s recycled collages combined canvas strips with text and images from popular culture—James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley—in a manner that anticipated the 60s Andy Warhol. In her text, Ray Johnson: Correspondences, Donna de Salvo compares Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines to Johnson’s early collages, noting, “If Rauschenberg introduced life into art, Johnson introduced art into life.” After Marcel Duchamp, Ray Johnson was one of the first artists “to utilize instructions for active participation in the artwork into the artwork itself.” His interest “in codes, poetics, and semiotic systems looked back to Duchamp while anticipating the contemporary practice of appropriation.”

Over the next decade, Johnson made a series of anti-rectangle collages. It wasn’t long before Johnson was mailing out collage fragments “for others to use or send on,” letting go authorship (at least in part) and allowing the work to be formed by increasingly random collaborations. No coincidence, then, that Johnson made this creative leap during his transition from Black Mountain to New York City while hanging out with his BMC buddies. Though a vital and experimental community, Black Mountain College was a bit of a mirage, isolated in many ways. For such an event-based artist, the late night dances were great but couldn’t beat the Ur-city’s cornucopia of experience that provided Johnson with such abundance. In both instances, he was surrounded by artist friends and mentors, immersed in their scenes. “With Manhattan as his field,” William S. Wilson writes, “Ray was disciplining himself to find uses for almost any accidental event.”

With all the myth and lore surrounding Ray Johnson and his theatrical suicide, it may seem to a young artist today that Johnson popped, fully formed, out of the head of modern art. But of course, as with all great artists, the young Johnson has his training ground. With our proposed show, “From BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson (1948-1958),” we will trace a circle around a decade of Johnson’s early art, spotlighting his explosion from talented painter and master collagist status to, by the 60s, Grand Dean of Dada & Postal Art. Indeed, Johnson’s time at Black Mountain College can be viewed in retrospect as a platform from which he dove into the vibrant world of New York City and its art world.

+copy.jpg)