You are going to find that studying Ray becomes

a discovery of yourself…yet also a revelation

of yourself to others.

William S. Wilson

Note 1

Bill Wilson, long-time friend, scholar and collector of Ray Johnson, wrote the above at some point early in our correspondence concerning all things Ray Johnson. The remark came both at the beginning of one of his famously long emails and early in the exhibition's curatorial process. I read it as a warning—a little wisdom from a long-time expert in the field, a curmudgeon’s scold directed at a first-time curator blithely sauntering in. A polite but firm, "Don't mess this up, kid."

And he was right to warn me. A lot goes into putting together an exhibition, more than I could have imagined, and the task only gets more difficult with an artist like Ray Johnson. For starters, the people who collect Ray’s work all have a unique and complicated relationship to Ray. Many of them were his friends, supporters, fellow Black Mountain College students; most want to preserve his legacy and, therefore, despite their generous lending, approach the process with trepidation. I am sure this is true in collecting work from any deceased artist, but there is something about Ray’s own famously ambivalent attitude to exhibitions and the art “biz” as a whole that adds a whole other layer to the project.

Add to this my sense of Ray as an artist (and how he will be considered in the future) which has been altered in a continuous revision process such that I no longer think of his famous bunny heads and mail art envelopes as trademarks of his work. I view them, instead, as buds blossoming at the tip of a branch of the flowering tree. For me, for now, it's Ray's early love of letter writing and doodling, his dramatic move away from painting—as well as his fascination with "glyph" markings, cutting up things, his verbal and visual reversals, his incessant punning—that exemplify the fundamental nature of his work.

Since receiving Bill’s warning, I have spent a year studying Ray and his time at Black Mountain College, on up to his subsequent move into Manhattan’s East Village art scene, and in that time have grown curious how the artists and fellow students Ray encountered along the way impacted his developing creative process. What do we gain, if anything, by examining Ray’s early output in light of his tutelary influences—the people and places that influenced him the most? Can we learn anything at all about an artist by looking into his early work—into the roots of his obsessions, his early propensities, the first major shifts in form and technique? Is the bloom of the later really found in the seed of the former? I tend to say yes to all the above. But why? How?

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

+copy.jpg)

Ray Johnson, James Dean/Rimbaud, collage on cardboard, ca. 1956-58, 11 by 7.625 inches, Private Collection

Tesserae 2, 1962 (William S Wilson)

Collection of William S. Wilson

(Estate of Frances X. Profumo)

Hazel Larsen Archer (Collection of William S. Wilson and John Wronowski)

(Estate of Frances X. Profumo)

Photo by Marie T. Stilkind

A Blog for the Exhibition, From BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson (1943-1967) Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center, Asheville NC

February 19th - June 12th, 2010

Ray Johnson piece at Blackbird Journal

Go online to www.blackbird.vcu.edu/

in the Gallery section

to read about the recent Ray Johnson show

held last spring at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

All work of Ray Johnson on this site is used by permission of The Ray Johnson Estate

+copy.jpg)

Ray Johnson, James Dean/Rimbaud, collage on cardboard, ca. 1956-58, 11 by 7.625 inches, Private Collection

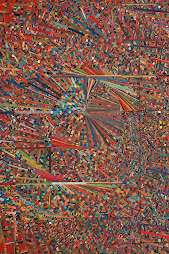

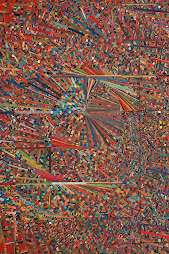

Detail from a Ray "Tesserae"

Tesserae 2, 1962 (William S Wilson)

Mat Fragment

Detail of Ladder Whirled (1952)

Collection of William S. Wilson

Links

- Asheville Vaudeville

- Barbara Cushman.com

- Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

- Charles Farrell, Collage

- Conversation with Ray

- Early Ray Johnson Interview in Detroit

- Essay on Ray by Mark Bloch

- Lauren LaRocca's article on Write Soon, Goon

- Merz Pictures

- Poetix Vanguard

- Raleigh Rambles

- Ray Bibliography

- Ray Exhibition from 1999, Review

- Ray Johnson - Educator

- Ray Johnson Estate

- Rayocide--67 Paragraphs on the Death of Ray Johnson

- Stealing Experience: A Collaboration in Friendship

- William S. Wilson on Ray's NYCS

MOTICOS, Shot by Avery the Imp

a Bunny Chart

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(139)

-

▼

January

(24)

- Just One of the Many Ray Johnson Pieces You've Nev...

- Rough Draft of Card # 5

- Krista Franklin Coming in February to Give Collage...

- Visual Poetry Workshop, February 27th at BMCM+AC

- Chicago-based Poet and Collagist, Krista Franklin

- Stay Tuned!!

- Ha Ha

- Early Altered Postcard

- from Code Word: Ray, by Kate Erin Dempsey

- Ray's Code

- Outtake from "Message(s) in a Bottle: Notes of an ...

- What is a Moticos?

- Decoder Ring

- Opening of Kate Erin Dempsey's "Code Word: Ray"

- Draft of Exhibition Poster

- Ray Mask

- "Negroes, Churches, Stars"

- Brief Excerpt from: Notes of an Unlikely Curator, ...

- Elegy for Ray

- A Peek at "Notes of an Unlikely Curator"

- Oedipus (Elvis 1), Ray Johnson

- No title

- "To Kate"

- Outtake from "Message in a Bottle: An Intro," on K...

-

▼

January

(24)

Ray's Mouth, Close Up of Archer Photo

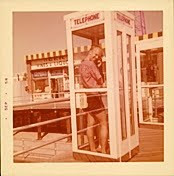

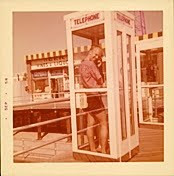

Ray in Booth

(Estate of Frances X. Profumo)

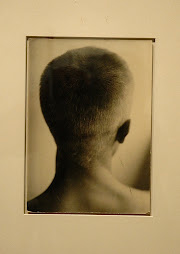

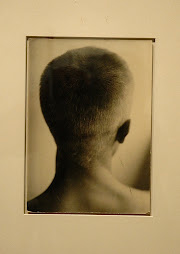

Back of Ray's Head

Hazel Larsen Archer (Collection of William S. Wilson and John Wronowski)

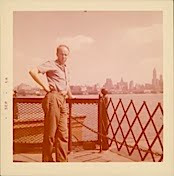

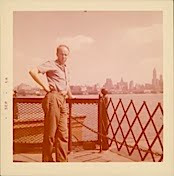

Ray on Ferry

(Estate of Frances X. Profumo)

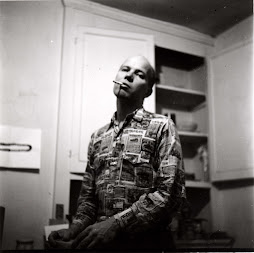

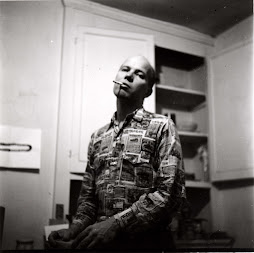

Ray in NYC Apartment

Photo by Marie T. Stilkind

detail from "Ha Ha," Collection William S. Wilson

BMC sandals