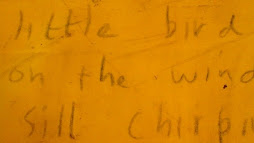

Ray Johnson played with language. In every medium, he gave letters and words a life of their own. As Clive Philpot has said, Johnson “attenuated and distorted the ability of words to identify and name things.” He delighted in puns, rhymes, anagrams, palindromes, spoonerisms, homophones, homonyms, and words within words. Even in conversation Johnson would reverse letters and let the discussion follow the new word, often leaving his interlocutor behind. He also played with the multiple meanings of words, enjoying how the alternative definitions spun off in every direction. In explaining his creative process he remarked: “I’m always rushing to my Webster’s Third Dictionary.” While this implies a love for the English language, Johnson once told a friend “We need new language. I’m so sick of this stuff.” Throughout his work Johnson highlighted the arbitrary nature of language by both shedding light on words we normally take for granted and turning seemingly transparent language opaque. Perhaps in an effort to invent a new language, Johnson peppered his work with codes, decipherable and otherwise. The role of secret languages in Johnson’s work remains relatively unexplored despite the fact that while looking at a display case of decoder rings in an antique store Johnson explained to Nick Maravel, his friend and videographer,

The whole basis of the New York Correspondance School... has to do with these secret messages coming over the radio and code systems. ...The participatory nature of writing these things down and getting messages. It's an "in" thing, a secret thing.

_______________________________________________________

Clive Philpot, “The Mailed Art of Ray Johnson,” in Phyllis Stigliano and Janice Parente, More Works by Ray Johnson (Philadelphia: Goldie Paley Gallery, Moore College of Art and Design, 1991), 46.

William S. Wilson, conversation with the author, June 2005.

Johnson, as quoted in Sevim Fesci, “Interview with Ray Johnson,” Archives of American Art Journal 40 (2000): 22.

Mark Bloch, “Rayocide: 67 Paragraphs on the Death of Ray Johnson,” originally prepared for Lightworks Magazine in 1995, http://www.panmodern.com/rayjohnson/rayocide.html (accessed 20 April 2006), no. 28.

+copy.jpg)